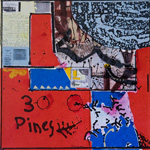

MICHELLE COLLOCOTT

Michelle Collocott in conversation with Steven Miller

SM: The whole series is called

MC: Three Ponds. The works in this exhibition are series C, part B. Series A was topographical and aerial. There were about fifteen of those. Series B was about the impact of the drought, the dryness in 2002. There were only eight or nine paintings here and they weren’t large. Then Three Ponds, series C, came at a time when I knew that I had to make changes again. The first fifteen paintings were shown last year, and these are the last fifteen.

SM: Maybe people don’t know about Three Ponds, the place

MC: Central Tablelands; sub-Alpine climate; an area generally called Black Springs; seasonally affected, so that you get the full range from the winter and the snow through to the rolling summer climate, with fields and hay.

SM: And when did you first get property there?

MC: We have to think in terms of my first discovery of it, which was after 1969, coming back from England, knowing that a sense of the dimension of the seasons was going to be important, and looking everywhere from the Northern Tablelands down to the Victorian border.

SM: What comes first, the landscape and then the artwork? How do they feed into each other?

MC: Knowing who one is, in the sense of what makes you tick, and then finding those places or those mechanisms that accentuate your passion, then as an artist you can start to play with it like theatre. It becomes a set, you’ve got the weather and the climate which create the dimensions of theatre, and then you transfer all that back into painting.

SM: And why has landscape been a constant theme in your art?

MC: That’s my childhood. I still come back to the idea of who we are comes from our childhood The paintings don’t set out to be true to place, other than being a mechanism and a structure to work inside of. The structures are related Michelle Collocott in conversation with Steven Miller to place, but the way the paintings evolved and developed just became part of the studio environment.

SM: There is quite a lot of text in them.

MC: They are also multi-layered, in that you’ve got images within images. You’ve got repeats. It’s like looking down a well. I’m interested in the ripple effect and although they are two dimensional and flat, what I like is the idea of layering, like looking into water. You stand on the edge of your dam and you see the water and then maybe you see a fish and then you start to see the reflections behind it, the barns and the trees.They are also in four parts which had to be joined back together. Digital scanning only allowed certain sizes of paper.

SM: A digital scan of what?

MC: Of an original sketch, of a tiny original sketch.

SM: But they don’t all use a digital scan, some of them are direct paintings onto the surface?

MC: They all have the digital scan.

SM: So in a sense you are working from a sketch as the basis for the works.

MC: I suppose, but it is all one sketch. If you look at every one, you will find a part of that original sketch They are simply a vehicle for one person’s journey, using certain technical skills that were passed on to me at East Sydney, when I was at the art school 50 years ago. That’s all it is. Amongst them, hopefully somebody will think “that’s a good painting’. I have no sense of whether they are worthwhile paintings or not.

SM: No, I’m sure you do. MC: No, I don’t. It’s quite subjective.

SM: Subjective, but not totally random. They are created and orchestrated.

MC: Yeah, but you have to work that out. I don’t know that.

SM: But when you are working on one you are making these decisions all the time: where is this going to go. You were talking about the repeats and echoes.

MC: When you are working on them, you don’t sit back thinking of those things. I am inside them…I love this idea of playing around with layering. You are guiding the eye through and over things. Is this on top of that or that on top of this? You get an oscillation between surface levels. Then you have license to do something lyrical, so you stick in some birds. You might go from the cerebral and meaningful to just sticking in some birds or a worm. Every now and then you need something structural, which is divisive, to change the rhythm of the surface. If the red is that strong, you really need something to bounce against it, otherwise the red just swallows the whole surface.

SM: Formal considerations; this proves that you give very serious thought to these things.

MC: That’s my problem.

SM: I don’t see it as a problem.

MC: It’s a problem for me, because I would like to be another sort of painter.

SM: Every painter wants to be another type of painter. You would like your work to be looser.

MC: I suppose. This is a problem with being a painter. You basically want to stretch your parameters all the time, either perception wise or physical wise or application wise.

Steven Miller is Head Librarian Research Library and Archive Art Gallery of NSW

NEST, exhibition and performance by Theresa Byrnes

6 January -17 January - with a performance on 14 January 7pm sharp

At Wilson Street Gallery Newtown, Sydney Australia

In its new exhibition, NEST, Wilson Street Gallery presents the recent paintings and a performance art piece by Australian Artist Theresa Byrnes. Byrnes has been based in New York for 10 years and this is the first performance she has done on Australian shores for 22 years.

Maura Reiley Ph.D, senior curator, American Federation Of Arts commented in 2007:

“Like Schneemann, Byrnes’ work is often characterized by critics as ‘body art’–a term that describes how artists will use their bodies as a literal canvas for enabling political or social commentary.”

This notion is punctuated by Byrnes in one of her most recent pieces called Trace (2007), a performance in which Byrnes submerged herself in a vat of crude oil, and then spent 30 minutes cleaning herself of the thick substance in front of a crowd of spectators on a New York sidewalk. In Boston Byrnes will be performing a new work titled Theresa Tree, a piece that she writes us is based on a question from her childhood: “What is the difference between me and a tree?” A worthwhile investigation indeed.

Byrnes’ painting leads her to a performance and at times performance will come first and act as herald as it ushers forth a series of paintings. For Byrnes both painting and performance art are a means of exploring ideas and understanding better the mechanics of humanity.

Byrnes examines in her latest body of work Nest, our instinct for security and home and contemplates how survival has become double edged. “Home, love and procreation come at the cost of entrapment and servitude to a global economy based on the assumption of ownership.” Theresa Byrnes said. “The other way of survival is through the indigenous understating of custodianship, “ she said. “In Nest, I use my hair to make my mark in the paintings and in the performance, to prove my being. I build, I paint a nurturing surrounding and find security in my own genetic rope: my hair.”

Byrnes’ ink on paper Nest paintings are intricate and soft; they conjure dream-like buoyancy or the heavy weightlessness of the depths of the sea. In them we see plants and creatures, cloudlike spirits and forms with the seriousness of blood and entrails, fractals and ferns. They are poetic and persist in their flowing detail to convince us of their simplicity.

Byrnes has established a firm place in the international arts community. Her work is part of the course-work at the San Francisco School of the Arts. She has won 2 Pollock-Krasner art awards and is widely collected.